A botched attempt at free climbing the storied ‘Sydney Route’ (16) on one of Australia’s biggest cliffs

In March 2021 I travelled to Tasmania with Ryan Castel, with the objective of free climbing one of the longest rock routes in Australia. At ~380m and ~13 pitches, the Sydney Route was not just going to be a challenge in rock climbing endurance. Tucked away in the remote western edge of Tasmania, Frenchman’s Cap has a long and challenging approach, as well as fickle alpine weather in one of the wettest places on earth. Despite my best efforts to research the route, the available information was not particularly detailed and so my understanding of the approach, climbing, protection and rock quality was vague at best.

We arrived in Tasmania in the middle of a three day weather window. With limited time to send the route, we decided to walk the full 23km approach to Tahune Hut in one day, and climb the route the following day. We knew if we didn’t climb the day after our arrival in Tahune Hut, there would be no more chances given a cold front was approaching.

The approach to Tahune hut was challenging even with great weather and a recently improved track, given the 25kg packs we had to haul in with rope, rack, food and camping gear. I’m extremely grateful to the folks who work so hard to maintain this track, as it has been made much easier by avoiding the need to wade through chest deep mud in the ‘Sodden Loddens’.

After arriving at Tahune Hut we sorted our gear and crashed early. We hadn’t yet had an opportunity to scout the route or the approach, given the 12 hours it took us to get to the hut from the road. Awaking the following morning at 6am, we were greeted with perfect weather and spectacular views. With some trepidation we started walking up the main hikers trail that goes towards the summit, unsure of what the approach would be like nor what the climbing would entail.

We found there is a relatively well beaten climbers track that veers off the main hikers track along the bottom of the cliff, however this becomes more and more vague as one traverses from the northeast to the southeast face.

After about an hour of traversing and questioning where the route started, I started leading the first pitch, hoping that we had found the right part of the cliff. It was one of the most serious and dangerous pitches I have ever lead. The rock was mostly seeping and wet, with frequent patches of moss and vegetation. The quartzite rock was loose and friable, with barely any positive holds. This required me to rely solely on footwork to stay attached to the cliff.

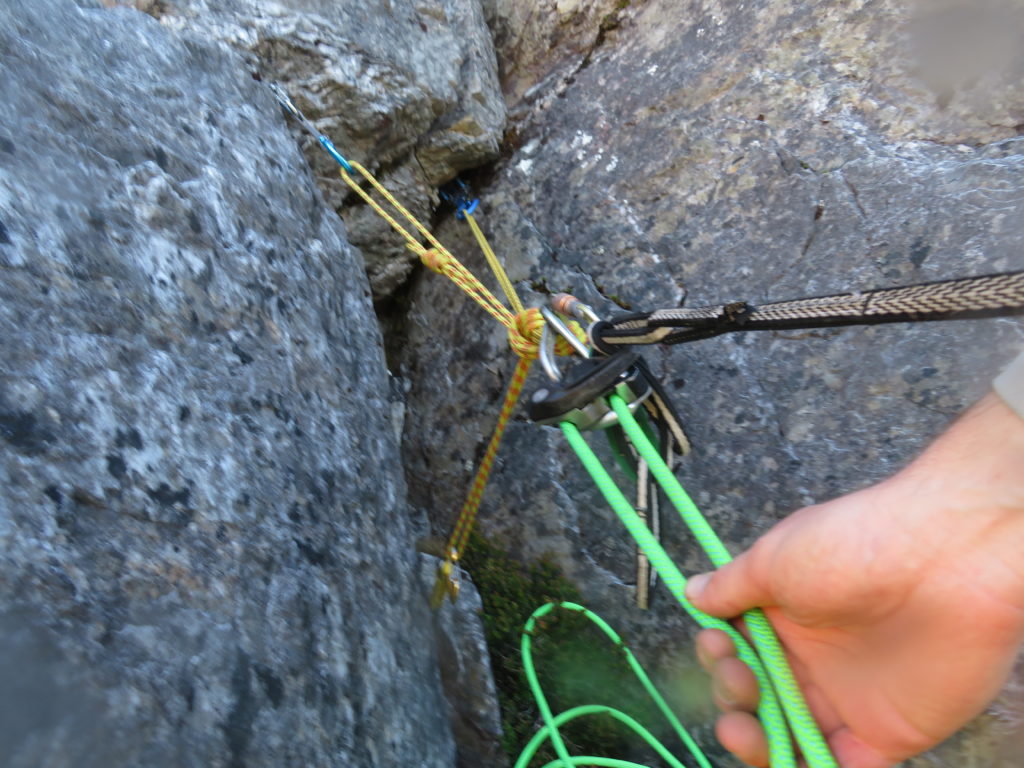

Most frustrating though, there was barely any good gear. I placed marginal pieces about once every 10m. Sometimes the blocks moved when I placed a cam in the adjacent crack. After 40m of delicate “no fall allowed” climbing, I finally got relief from the feeling I was going to die when I topped out on a small ledge and could construct a solid anchor.

When Ryan joined me on the ledge, I pulled up and continued on. I was greeted with a large mossy shelf and climbing that looked even worse than the first pitch. The entire wall in front of me was covered in wet moss, and was composed of the most rotten and friable rock I’ve ever tried to climb. I thought it surely must improve a bit higher up, but after climbing a bit higher and feeling like my life was about to be disposed of, I downclimbed back to the ledge and we made the call to abseil back to the ground.

I was disappointed that we didn’t get beyond the first pitch, as we had trained for this route for the better part of summer. But our training was clearly inadequate given the demands of the climbing. In the end we felt we had to bail, the risk was beyond our tolerance level and knowing that the weather window was closing fast, we didn’t want to end up trapped on the face in a storm. We spent the rest of that day traversing the cliff trying to scout the line and other lines, before heading up to the summit via the hiker’s trail.

On day 3, we spent the day resting in Tahune Hut watching the wild Tamanian weather turn foul. The temperature plummeted to near zero, and the following day on our walk out we did observe some snow on the trail. Disappointed as we were to be shot down by the climbing, the walk out was spectacular as the stormy weather cleared.

I am fascinated to hear from anyone who has completed this route. I suspect that it doesn’t have the best rock on Frenchman’s Cap, but it probably gets the most attention given it’s length and intermediate technical difficulty (though it was definitely sandbagged). Given the chossyness of the rock, I’m not particularly inspired to go back to Frenchman’s Cap for rock climbing in a hurry, maybe one day if I meet someone who has done lots of climbing there and can show us the way.

Ben Lomond

We followed up our micro-adventure at Frenchman’s Cap with some fun cragging at Ben Lomond. This was much more civilised with great rock quality, solid protection, and high friction jam cracks. Probably the best crack climbing I’ve done within Australia, definitely worth returning for.